Ancient Canadian Rocks Could Be the Oldest Known on Earth

Geologists have discovered ancient rocks in northern Canada that may date back over 4.2 billion years, possibly making them the oldest known rocks on Earth and offering new clues about the planet's early formation.

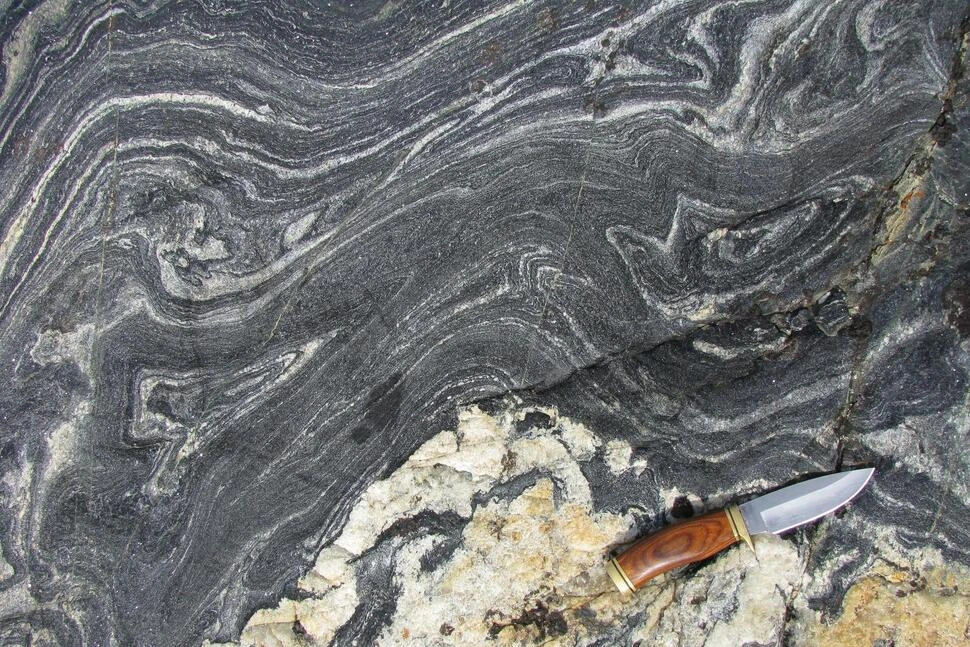

A team of geologists has identified what may be the oldest known rocks on Earth, found in the remote wilderness of northern Canada. These ancient formations, located near Hudson Bay in the Canadian Shield, could be more than 4.2 billion years old, pushing back the timeline of Earth’s solid crust and offering rare insight into the planet’s earliest history. The rocks were uncovered in a region of northern Quebec, already known for some of the oldest geological formations on Earth. But new analysis using advanced geochemical techniques suggests that this specific outcrop may predate all others previously studied — even older than the famed Acasta Gneiss in the Northwest Territories, which dates to about 4.03 billion years ago. A Geological Time Capsule The newly analyzed rocks are composed primarily of tonalite gneiss, a type of metamorphic rock that forms deep within Earth’s crust. Researchers were able to isolate zircon crystals trapped within the rock layers — microscopic time capsules that can survive billions of years of geological change and are critical to radiometric dating methods. Using uranium-lead isotope analysis, scientists found that some of the zircon samples pointed to an origin as far back as 4.28 billion years ago — only a few hundred million years after the Earth itself is believed to have formed. “This is a remarkable discovery,” said lead geologist Dr. Marianne Dupuis, who headed the study from the University of Montreal. “We’re essentially looking at fragments of Earth’s primordial crust. These rocks are telling us a story from a time when the planet was still molten, turbulent, and barely beginning to form the crust we live on today.” Rewriting Earth’s Timeline If verified, the discovery could reshape the scientific understanding of Earth’s early evolution. Until now, most evidence of Earth’s crust from the Hadean Eon (the planet’s first 500 million years) came from detached zircon grains, rather than intact rock formations. What makes this find so significant is that it may represent a surviving portion of the planet’s first continental crust — offering scientists a rare opportunity to study the chemical composition, formation conditions, and geologic processes of Earth’s infancy. “We’ve had slivers of the story before,” said Dr. Dupuis. “Now we might be holding the actual pages.” The study also opens the door to new theories about when plate tectonics began, how the Earth’s early atmosphere and hydrosphere developed, and what conditions might have first made life possible. Surprising Chemical Signatures The geochemical profile of the rocks is also sparking scientific debate. Researchers found isotopic signatures of elements like neodymium and samarium that differ from younger continental crust, indicating a very different chemical environment billions of years ago. More intriguing still, some scientists suggest that the rocks show traces of interaction with water, hinting that Earth’s surface may have hosted liquid water — and possibly even the earliest forms of microbial life — much earlier than previously believed. “This could change how we think about the timeline for habitability on Earth,” said Dr. Leon Kim, a geochemist at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study. “If water was present when these rocks formed, it suggests the planet stabilized faster than we thought — and that life could have begun sooner than we imagined.” Remote and Resilient The discovery site lies in a rugged and largely inaccessible part of Quebec’s far north, reachable only by helicopter during a short summer window. The Canadian Shield — a massive, ancient geological formation stretching across much of eastern and central Canada — is one of the few places on Earth where Archean and Hadean rocks can still be found at the surface, preserved through billions of years of tectonic upheaval and erosion. The rocks were first sampled in 2023 during a survey of unexplored shield regions but only recently dated with high-precision equipment. Future expeditions are planned to collect additional samples and explore nearby outcrops for related formations. “These rocks have withstood unimaginable pressure, heat, and time,” said Dr. Dupuis. “It’s humbling to think they’ve been here since the dawn of the Earth itself.” Implications Beyond Earth The implications of this discovery extend beyond geology. Understanding how Earth’s early crust formed could also offer clues for studying other rocky planets, including Mars, Venus, and even exoplanets beyond our solar system. “By studying the oldest rocks on Earth, we can learn what to look for on alien worlds,” said planetary scientist Dr. Eva Morales. “It helps us understand not just how Earth became habitable — but whether similar processes might be occurring elsewhere in the universe.” NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) have both expressed interest in collaborating with Canadian researchers to develop comparative studies that bridge planetary science and geology. What’s Next? The research team plans to publish its full findings in a peer-reviewed journal later this year, and an international team of geologists will be working to validate the dates and further analyze the chemical structure of the zircon crystals. If verified by the global scientific community, the Quebec rocks may take their place as Earth’s earliest physical testimony — a piece of stone born before any life stirred, continents drifted, or oceans formed. “This is the beginning of something much larger,” Dr. Dupuis noted. “It’s a puzzle piece from a time we’ve only glimpsed through chemistry and theory. Now we can touch it, hold it, and learn from it.”